Many fiscally sponsored projects ask their sponsors to manage their crowdfunding campaigns, so backers get the benefit of a tax deduction. Others crowdfund on their own, forgoing the tax incentive. This story explains both approaches.

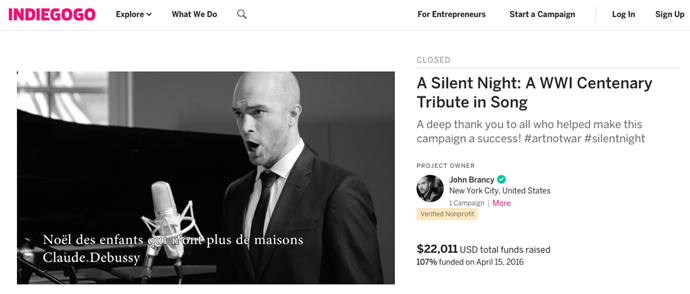

Baritone John Brancy records classical songs for “A Silent Night,” an album that honors the millions of soldiers who lost their lives in the Great War. Fractured Atlas fiscally sponsored the project to produce the album.

Fractured Atlas provides Model C fiscal sponsorship to arts and culture projects of all sizes from coast to coast, and offered crowdfunding exclusively through Indiegogo. That changed last year when it began shifting crowdfunding to its own site through its own app. Today, Fractured Atlas projects can use any crowdfunding platform they want but must use its app if they want to offer campaign backers a tax deduction.

During its seven years with Indiegogo, Fractured Atlas’ projects ran 2,929 campaigns that raised more than $13 million. One campaign was for the album “A Silent Night,” a tribute to composers who lived through, fought and died in World War I, produced by baritone John Brancy and pianist Peter Dugan, which raised $22,011.

Another brought the Philadelphia Argentine Tango School $12,375 to replace its plywood floor with durable hardwood. More modestly, Driveway Follies raised $7,025 for its annual Halloween show in an Oakland driveway, complete with intricate puppets, backdrops, props and sets built by hand.

Fractured Atlas’ biggest Indiegogo campaign, said Dianne Debicella, former senior program director, was for “No Greater Love,” a documentary made from footage of fighting in Afghanistan and interviews with returned vets, released in October 2015 after raising $107,000 from 1,619 backers.

“Some donors just don’t care about tax deductions.”

— Lisa Burger, President and Executive Director, Independent Arts & Media

Despite such successes, some Fractured Atlas projects had decided to fly solo on other crowdfunding platforms without their fiscal sponsor, forgoing the tax-deductibility incentive for donors and avoiding the 7% sponsorship fee.

Debicella said Fractured Atlas didn’t keep statistics on how many had chosen to campaign outside Indiegogo, but many had used Kickstarter “for its brand recognition and for the perception that it seems to be specific to the arts.”

One such solo project was Groupmuse. Since 2013, it has facilitated thousands of concerts nationwide by young chamber musicians, many at in-house parties that draw fewer than 20 people. Groupmuse’s crowdfunding campaign in November 2015 had a goal of $100,000 but brought in $140,000 from 1,478 backers, “the biggest classical music Kickstarter in history,” Groupmuse founder Sam Bodkin said.

Unlike Model A fiscal sponsorships, Model C projects can maintain their own bank accounts, and donations needn’t be deposited in their fiscal sponsors’ accounts.

How Kickstarter Works

Kickstarter claims to be the biggest crowdfunding platform anywhere — 144,000 fully funded campaigns by artists, musicians, filmmakers, designers and other creators who have brought in $3.26 billion since the platform started in 2002. Of the 14.6 million people who have backed Kickstarter campaigns, more than a third are repeat contributors. Still, only 36% of campaigns are fully funded. That’s close to the average 40% success rate for crowdfunding globally cited by several sources.

To date, Kickstarter’s largest campaign in all categories was to develop Pebble Time, an “Awesome Smartwatch,” says its promotion, that raised more than $20 million from 78,000 backers. In film, the biggest was a project to bring back Mystery Science Theater 3000, which ran from 1988 to 1999 on a Minneapolis television channel — 48,000 fans pledged $5.7 million.

Kickstarter is an all-or-nothing platform. With fees comparable to Indiegogo and GoFundMe, it collects a 5% platform fee plus 3% and 20-cent transaction fee for its “payment partners” — if the campaign gets fully funded. If not, the project gets none of what’s been pledged and pays no fees.

The platform takes pledges through Stripe and charges the backer’s credit card only when the campaign reaches its funding deadline and meets its goal. Unlike a donation to a nonprofit on a website, which is charged to the cardholder immediately, crowdfunding support is a pledge, and the amount isn’t charged until the campaign ends.

Kickstarter sends no tax receipts. On its site, it tells backers wondering if their pledge is tax-deductible: “In general, no. However, some U.S. projects started by or with a 501(c)(3) organization may offer tax deductions. If so, this will be touted on the project page. If you have questions about tax deductions, please contact the project creator directly.”

One of the largest Kickstarter campaigns mounted by a fiscally sponsored project the Directory uncovered was for McSweeney’s. The publishing house founded in 1998 by novelist Dave Eggers began life as a for-profit, but in 2014 opted for fiscal sponsorship through SOMArts in San Francisco.

The next year, McSweeney’s raised $257,080 from 3,419 contributors in a one-month Kickstarter campaign, using the donations to support all of its publishing projects as it moved toward becoming an independent nonprofit.

“Every year it gets just a little harder to be an independent publisher,” Eggers told San Francisco Chronicle Book Editor John McMurtrie, explaining his move to the nonprofit sector and fiscal sponsorship. “Now there’s the opportunity to raise money around a certain project or to write a grant for it, or even crowdfund for it.”

Which he did, with stunning success. The campaign reached half its goal of $150,000 in its first five days. The organization’s literary reputation meant it didn’t need tax deductions to attract donors. And, as a Model C project, with a bank account separate from SOMArts, it got to keep everything it raised, less the Kickstarter and transaction fees. By not having to pay SOMArts’ 8% fiscal sponsor fee, McSweeney’s likely kept as much as $20,000 in its pocket after paying almost that much to Kickstarter.

Filmmaking and crowdfunding

Crowdfunding campaigns are like wish lists that aren’t always fulfilled. Successful campaigns, says Lisa Burger, president and executive director of fiscal sponsor Independent Arts & Media in San Francisco, seem to have this in common: “They already have an online community in place to get the word out.” She thinks crowdfunding as a fundraising strategy will stick around and even grow for fiscally sponsored projects.

IAM has 60 fiscally sponsored Model A and Model C projects, and has been involved with 15 campaigns that combined brought in $89,000. One raised $10,334 from 73 backers for the preliminary work on “Still I Rise,” a documentary about a sex-trafficking survivor who becomes a national antitrafficking leader. The filmmakers started another $25,000 campaign on Indiegogo through IAM to fund editing and postproduction.

Though IAM has a good track record with crowdfunding, some of its projects simply aren’t interested in it, Burger says. The disincentive of paying up to 15% to 18% in combined platform, third party and fiscal sponsor fees may be part of it, but there’s more: “They don’t think it does them any good, and some donors just don’t care about tax deductions.” (The amounts pledged may be small, and the donors may not itemize deductions on their tax returns. One estimate is that only a third of taxpayers itemize.)

It’s a similar story at Women Make Movies, a New York fiscal sponsor. About 20 of its 250 projects, all Model C, have crowdfunded, estimates Barbara Ghammashi, director of WMM’s production assistance program, but only “a handful” of those ran campaigns through WMM. One was “Speed Sisters: Racing in Palestine,” a documentary about the Middle East’s first all-woman motor racing team in the occupied West Bank. It set a $35,000 goal for its 2012 Indiegogo campaign and raised $46,438 from 221 backers, most in the $25 to $100 range.

That wasn’t enough to finish the film, but partial funding gives producers some footage to show bigger backers. “Speed Sisters” eventually picked up other support and has been screened in film festivals internationally.

“We want our filmmakers to get across the finish line — whether the money goes through us or not.”

— Barbara Ghammashi, Production Assistance Program Director, Women Make Movies

Another Women Make Movies project, “The Story of George’s Curious Creators,” a doc about Hans and Margret Rey, the authors of the children’s classic book Curious George, ran an independent campaign and raised $186,010 from 1,483 backers on Kickstarter.

“Most of our projects don’t choose to have the money go through us because it takes a substantial percentage out of what they raise,” says Ghammashi. “However, we always encourage our filmmakers to include language in their campaigns letting potential donors know they can make a tax-deductible contribution directly through Women Make Movies. We want our filmmakers to get across the finish line — whether the money goes through us or not — so we always encourage them to let us know when campaigns are happening so we can promote them.”

Ghammashi believes what’s most advantageous about crowdfunding for filmmakers it that it helps them build their audience. “A successful campaign,” she says, “gives them metrics they can show funders, festivals and other potential supporters of the film that there is an audience waiting to see it get made.”

Marjorie Beggs is the Directory manager.