This isn’t the San Francisco setting depicted on colorful postcards of a city known for its beauty.

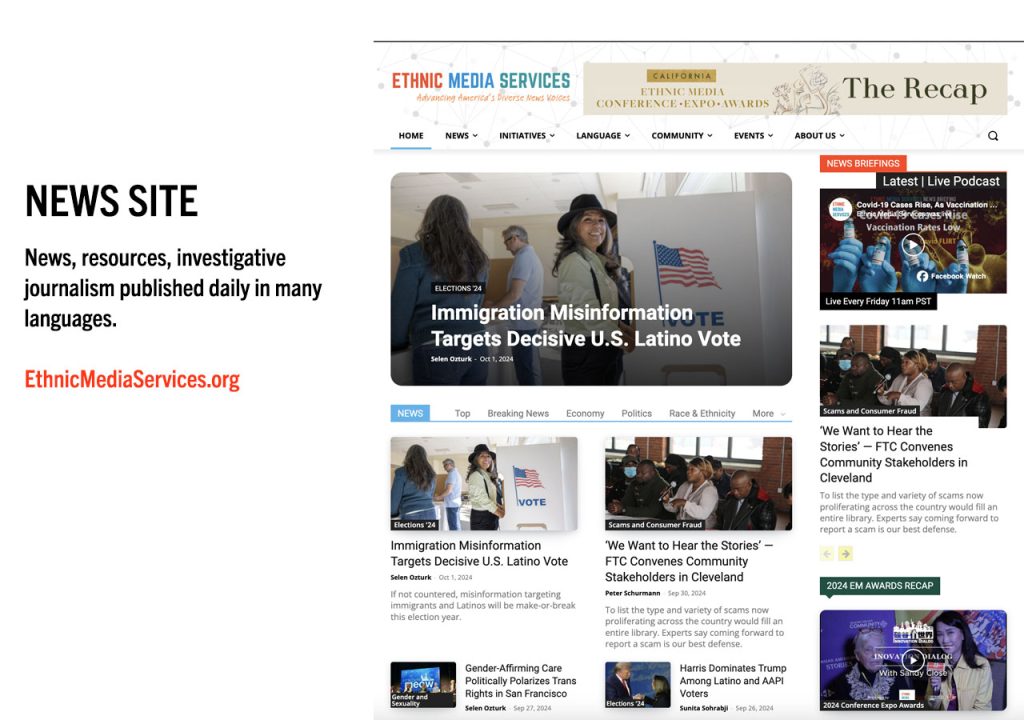

What’s vivid here, on trash-strewn Mission Street in a drab building a block from a traffic-clogged freeway, is the work of Ethnic Media Services. EMS is dedicated to informing today’s multicultural, multilingual America about critical, everyday topics, a goal so challenging and so pressing that it transcends the physical surroundings of a nonprofit’s well-worn office.

Ethnic Media Services was founded by Sandy Close in 2018 under the fiscal sponsorship of the pioneering San Francisco Study Center, first grassroots sponsor in the city. Her aim was to harness the power of ethnic media outlets nationwide, reflect cultural similarities and differences, educate stakeholders and connect communities of color to the civic life of the country – missions grander than EMS’ modest office, tucked inside the Study Center’s larger suite.

These lofty goals are in reach only because of Close’s perseverance, energy and experience. She’s been preparing for the challenge throughout her six-decades career as a journalist and nonprofit executive. Highlights of her bona fides: a MacArthur Award in 1996 for “developing innovative journalism on a shoestring budget,” that same year an Academy award as co-producer of a best short documentary about a polio survivor’s life in an iron lung, then in 2016 a prestigious George Polk Award for Career Achievement.

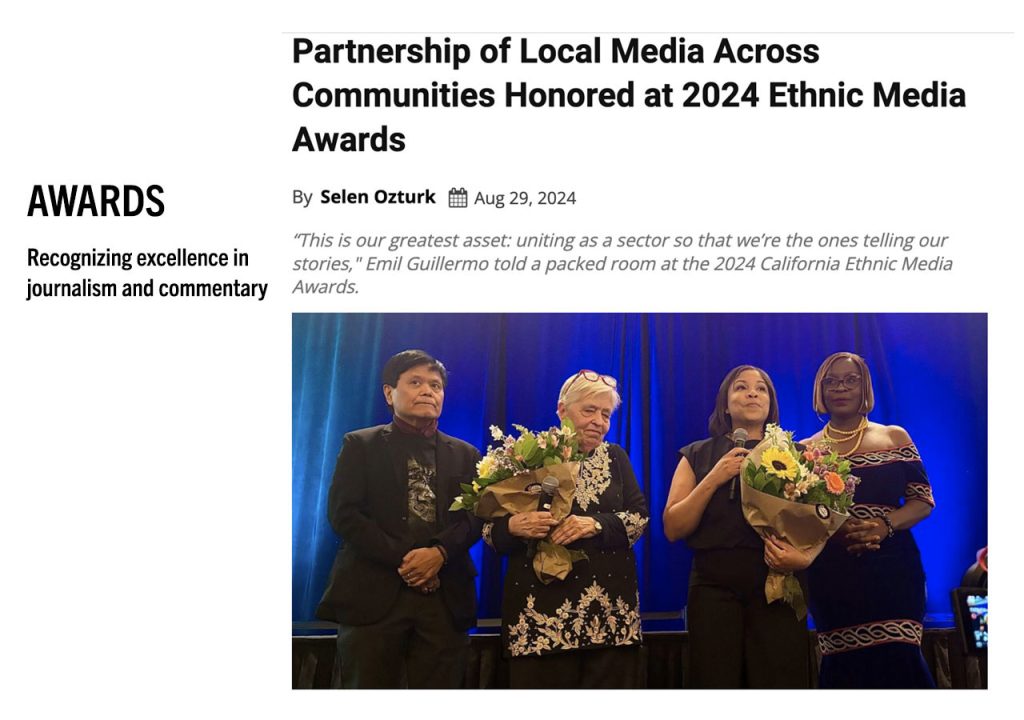

Sandy Close, left, and Regina Brown Wilson, right, executive director of California Black Media, present a Communications Champion Award to Tracy Arnold, Assistant Director at the Calif. Department of Health Care Services, at the EMS/CBM co-sponsored 2024 Ethnic Media Conference, Expo & Awards event. Photo: Peter Schurmann

Close, a Chinese Studies major at UC Berkeley, became a journalist in Hong Kong in the mid-1960s as China editor of the Far Eastern Economic Review. Returning to the Bay Area, she founded The Flatlands, a predominantly Black newspaper in Oakland. Beginning in 1974, she was editor/director of the groundbreaking nonprofit Pacific News Service. PNS embedded journalists in Southeast Asia during the Vietnam War to diversify the content of the mainstream press. She expanded PNS in the early 1990s to include youth voices. In 1996 she launched New America Media as the first and largest association of ethnic news outlets. After PNS and NAM closed in 2017, Close founded EMS to concentrate on the ethnic media sector.

Most Racially Diverse Program in America

Today, Ethnic Media Services’ directory lists more than 3,000 broadcast, print and online outlets and connects hundreds each week to timely topics that will benefit their communities. Major foundations such as Ford, Robert Wood Johnson, Blue Shield of California and the Houston Endowment, large nonprofits, and local, state and federal branches of government fund EMS to expand their reach.

Close brought Ethnic Media Services to the Study Center as a funds-poor startup in need of Model A fiscal sponsorship. Study Center is the rare major sponsor that takes on new projects that don’t have five-figure budgets. EMS today is the largest, most far-reaching of Study Center’s 40-some fiscally sponsored projects and, arguably, the field’s most diverse project: The ethnic media outlets it works with represent every race, language and culture publishing and airing in America.

“When we closed NAM and launched EMS, my desire was to promote the sector at a time when local journalism across the board was struggling. I wanted to devote full time to that, not to managing a nonprofit of our own.” — Sandy Close

Fiscally sponsored, Close can focus on “building a national hub for ethnic media” while Study Center handles the back office, administering grants and contracts and providing accounting, bookkeeping, taxes and human resources such as health care for employees.

“When we closed NAM and launched EMS, my desire was to promote the sector at a time when local journalism across the board was struggling. I wanted to devote full time to that, not to managing a nonprofit of our own,” Close told me.

She recalled that over lunch, Jan Masaoka, a long-time nonprofit expert, had suggested she seek fiscal sponsorship with the Study Center under Executive Director Geoff Link. Masaoka phoned Link right then.

His immediate response: “When can we start?”

Evolution of Ethnic Media Services

I met Close in her office at 7:30 one recent morning. Early for me, it was late for her. She’s usually there at 4 a.m., but it was after midnight when she got home from a job in Mississippi. What first struck me when I went to watch her in action was how long and hard she works.

“Every day seems like an easy day” before it starts, she’d said in conversation a few weeks before. This day, I find her sitting at a table in a windowless room, opening her computer, reaching into a large, green tote bag bulging with papers and the sort of office supply paraphernalia an organizer needs for meetings. When she isn’t traveling, she’s Zooming, which she does with practiced expertise. Today, as most days she’s working in San Francisco, she’s accompanied by Tinkerbell, her aged Chihuahua. Walking Tink is how Close gets her work breaks throughout the day.

She started her career as a journalist and has a deliberate manner of speaking, her words carefully chosen and put together with precision.

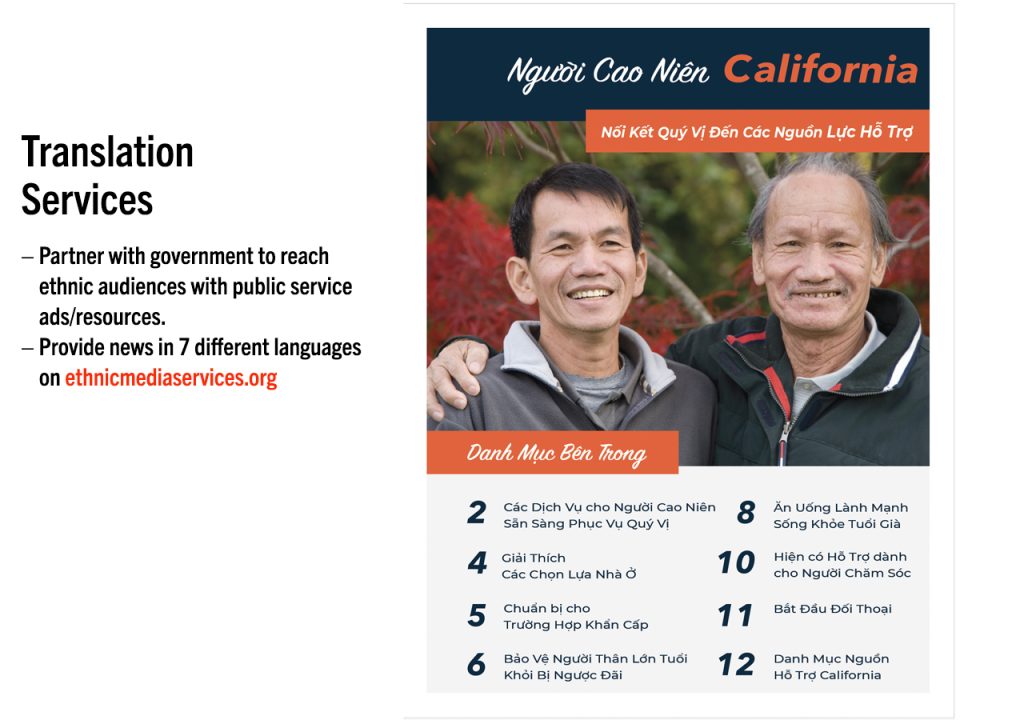

“How do you cross the language divides?” Close had asked when we talked previously. “How does the government communicate with the governed when the governed don’t speak a word of English? My sense is that the future for ethnic media lies in its abilities to inform and engage in areas that the government can’t reach through traditional media.”

The same is true for foundations. In the evolution of Ethnic Media Services, Close has shifted from relying primarily on foundation grants to finance her work to fee-for-service contracts. “It’s a more sustainable model than seeking one-time grants for our nonprofit.”

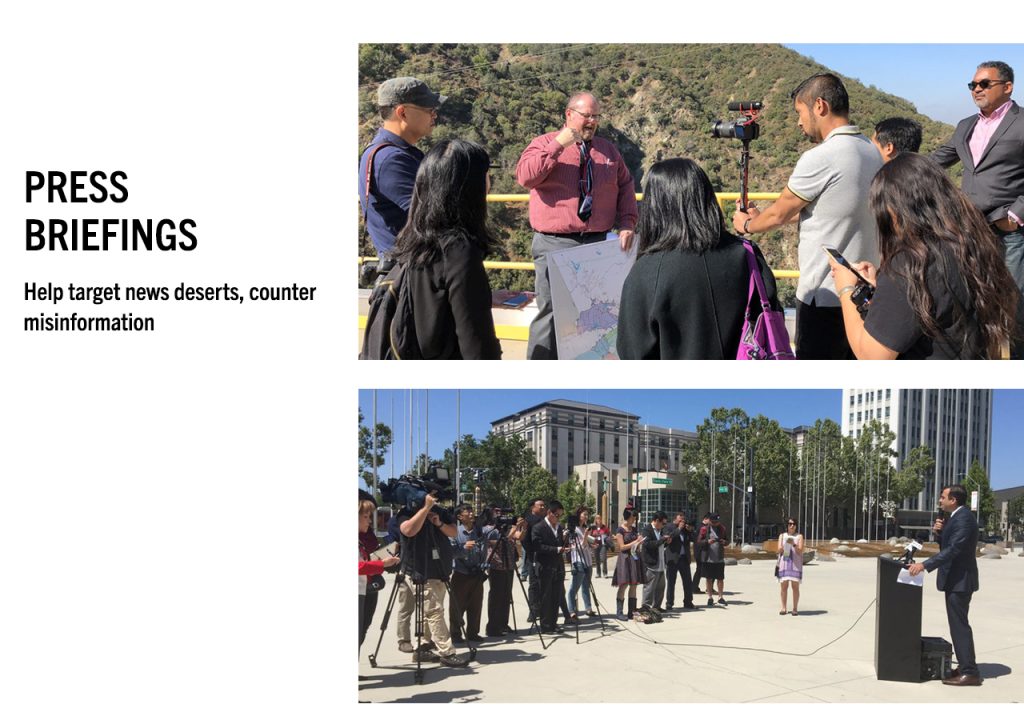

The pandemic turned out to be a breakthrough. It pushed EMS from organizing onsite news briefings to conducting online briefings. With a seed grant from Blue Shield, EMS launched weekly Zoom news briefings for ethnic media nationwide, first to track the pandemic, then to consider health care, economy, housing, education, foreign policy and voting rights issues.

Each briefing presents experts, advocates and newsmakers that ethnic reporters would have trouble reaching on their own. With simultaneous interpreting in Spanish, Korean and Mandarin, each briefing draws an average of 70 multilingual reporters who produce stories for their outlets. EMS syndicates a story from each briefing to its broader network along with video excerpts to post on social media.

The two-day 2024 Ethnic Media Conference included 12 sessions with panels of speakers active in ethnic media promotion and publications. Photo: Peter Schurmann

About 40 get-out-the-word EMS projects have been funded by government agencies, 20 or so large nonprofits and roughly a dozen foundations, some making six-figure grants. Every EMS contract includes funds to buy ads, pay fellowships to reporters for in-depth stories, and stipends for community participants, so the funders’ investment also subsidizes the communities they want to reach.

“The federal government’s ad budget is among the top 25 in the country,” says Close. “And PR people outnumber journalists by something like 10 to 1.” EMS journalists do the messaging work of PR firms but customize it to their unique audiences. “They’re journalists. They tell stories from the inside out so it resonates with their communities.”

Making Ethnic Media ‘Indispensable’

EMS can reach a wide variety of outlets in multiple languages. In California, these range from Indonesian Journal, a San Gabriel Valley weekly published by a dentist; Myanmar Gazette, the only Burmese news platform in the country, has 15,000 followers; Khmer TV in Long Beach; Lo Nuestro TV targeting Salvadorans in L.A.; Slavic Sacramento, which provides news in Ukrainian, Russian and Slavic languages; Chico Sol, “border-crossing journalism” online in Butte County; the Richmond Pulse, a Black-run platform specializing in youth voices; and Two Rivers Tribune serving the Hoopa reservation in Humboldt.

Ten years after New America Media ran onsite briefings in eight cities for the U.S. Census Bureau under a modest $60,000 contract, EMS coordinated California Complete Count’s 2020 $1.8 million (Check amount) outreach campaign to AAPI, Native American, Middle Eastern and North African media.

“For the first time, ethnic media were recognized as indispensable,” says Close.

EMS coordinated California Complete Count’s 2020 voter outreach campaign to AAPI, Native American, Middle Eastern and North African media. “For the first time, ethnic media were recognized as indispensable.” — Sandy Close

Then came the pandemic and the push to vaccinate the entire state. “We were able to connect government agencies like the California Complete Count and the Department of Public Health to media they never knew existed – like Punjabi Radio in the Central Valley, where Punjabi is the third most spoken language. And we leveraged ethnic media’s convening power with community organizations to create news events that the media could then cover.”

With the rise of anti-Asian hate crimes, EMS joined forces with California Black Media that serves more than 30 Black news outlets in California to coordinate a two-year, multiracial, multilingual Stop the Hate initiative funded by the State Library.

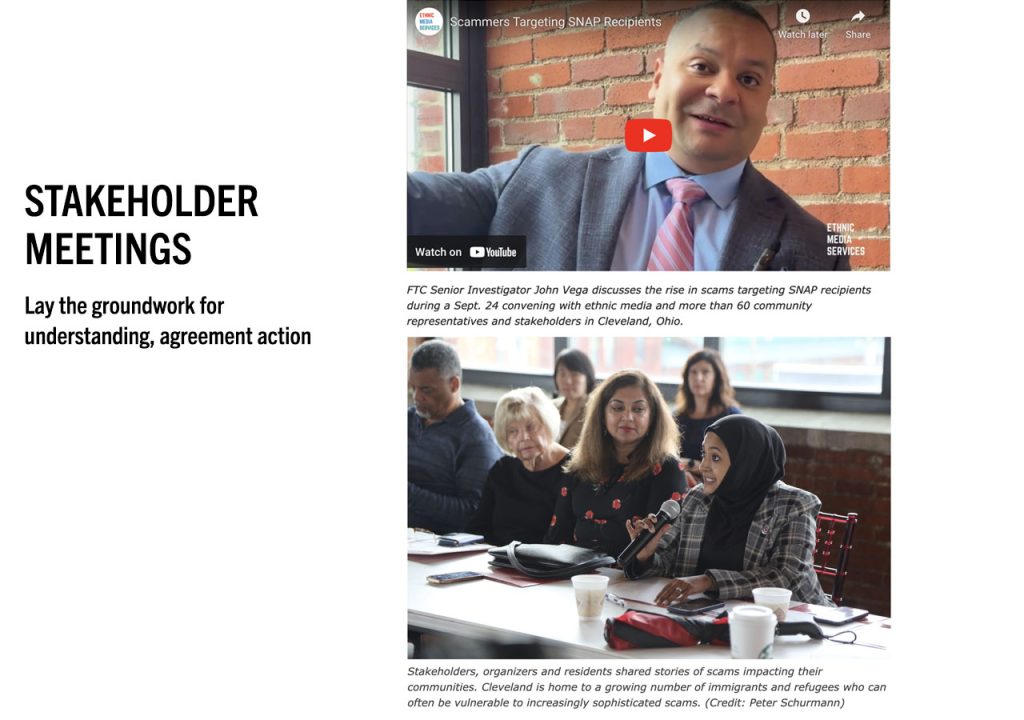

Close recently traveled to Boise, Idaho, and Jackson, Miss., where EMS organized onsite news briefings for the Federal Trade Commission to alert citizens to scams and how to avoid them; to Houston at the invitation of the local humane society to publicize how to deal with feral dogs; to the Somali Family Service of San Diego to publicize Medi-Cal’s expanded behavioral health services; and back to Houston for a news conference on gun violence. Bezos Earth Fund recently awarded UCLA a grant for an urban greening reporting project in which it will partner with EMS and L.A. County ethnic media.

The morning we met in her office, Close was Zooming with FTC officials to prepare for the July 24 conference on scams in Jackson.

“Some important people will be at the conference,” Close says, handing me a “Stakeholders and Community Influencers” list that includes the Mississippi Association of Community Action Agencies, Mississippi Council on Economic Education and Mississippi Immigrant Rights Alliance, as well as the Better Business Bureau and a dozen media representatives. “We’ve lined up in-person interviews with local Black radio, Spanish language media, and the Jackson Advocate, the oldest and largest Black weekly in the state. Grassroots groups are a high priority because they bring the storytellers,” she added.

When the Zoom begins, a participant asks Close for advice on the presentation.

“First and foremost, give people an overview of the consumer frauds and scams and the ability of the FTC to protect people,” Close says. “People don’t know how things work. When you are scammed, who do you tell? Who at the local level do you contact?” Telling stories of the top scams hitting Mississippi “would be catnip for the media,” she says.

‘You Are the Communicators’

After the Zoom, Close packs up a bunch of handouts and drives the two of us over the Bay Bridge to Laney Community College in Oakland. EMS and California’s Department of Health Care Services are hosting an event where two dozen Asian American and Pacific Islander students will learn that Medi-Cal has expanded its services — including traditional Asian healing such as acupuncture and massage — to all immigrants, regardless of legal status. Eight to 10 ethnic media will cover the event for Tongan, Filipino, Chinese, Spanish, Asian Indian and Korean audiences. Each student will get a $100 check for participating and then spreading the word about the Medi-Cal services.

The session’s aim is to let this AAPI group, which represents more than a quarter of Laney’s student body, know that while acupuncture was recently on the state budget chopping block, it will remain an essential Medi-Cal behavioral health service. David Lee, director of Laney’s Asian Pacific American Student Success program, Eric Yuan, deputy director of Alameda County Behavioral Health Care Services, and the official overseeing Medi-Cal enrollment spoke along with several healing arts practitioners.

A staffer from Radio Tonga, broadcasting since 1961, interviews a Laney Community College student at an EMS and Calif. Department of Health Care Services-sponsored event on available Medi-Cal services. Photo: Peter Schurmann

A crew from Radio Tonga is videoing the event for a radio segment and screening on its website. The Asian medical team Yuan invited starts setting up in the back of the room and speakers arrange their brochures and giveaways. The Alameda County behavioral health team puts free water bottles, computer easels and pens on a table. As box lunches of sandwiches arrive, the first students filter in.

“You are the communicators,” Close begins, “You’re here to learn what you don’t know and what you’ll share with families and communities. We were asked by the state agency for Medi-Cal to help spread the word that Medi-Cal is now accessible to all immigrants, whatever their legal status.”

She continues: “Not only don’t many people know what Medi-Cal is, but many don’t know what it does or how to access it. Your job today is to learn what you didn’t know.”

Asian American and Pacific Islanders make up nearly a third of the population of Alameda County, Yuan tells the audience, and one quarter of them report having behavioral health issues. Less than 10% seek care.

Close interrupts to ask him to define behavioral health. This gets things down to specifics. If the students have depressed or suicidal relatives or friends, Medi-Cal will provide health care services. It will even cover the cost of tattoo removal, (CHECK)

A significant number of ethnic media shut down during the pandemic. Close and EMS “literally helped keep the sector afloat, providing ad revenue for mom-and-pop outlets. Reporters covered EMS’ briefings, and the stipends allowed many to stay in the field.” — EMS health care reporter Sunita Sohrabji

At session’s end, while Close sits at a table at the front of the room writing out students’ checks, I talk with EMS health care reporter Sunita Sohrabji, a veteran journalist for India West, which folded in 2021. A significant number of ethnic media, including India West, shut down during the pandemic, Sohrabji says. Close and EMS “literally helped keep the sector afloat, providing ad revenue for mom-and-pop outlets. Reporters covered EMS’ briefings, and the stipends allowed many to stay in the field.”

As the room empties, Close finally relaxes and gets a hand-and-shoulder massage from one of the healers. “This is a first for me,” she says.

“You see why I like the ethnic media community?” she asks me on the drive home. “They’re not cynical. They’re here to get the information out to their audiences. Convenings like today aren’t perfectly scripted. But they’re authentic.”

She spends a good deal of time arranging things, counting on people to show up when they’ve promised to perform, to listen, and then to pass it on. Surely this reliance on volunteers must have resulted in disappointment from time to time?

“Usually, if people don’t show up they have a good reason. But I have rarely felt let down.

Even on taboo topics in their communities, they show up and cover them.”

Close dives into EMS’ next big project, a partnership with California Black Media: a two-day annual Ethnic Media Conference, Expo & Awards in Sacramento, with more than 300 attendees expected, including top state officials. Close checks on award submissions and finds out 310 entries have logged in – the most ever. (Read about the August 27-28 event here.)

At any one time, EMS is working on 10 active projects, with four or five on tap for the near future. It was Study Center Director Geoff Link who’d told me about EMS and Close’s determination and hard work.

“She makes it go and go and go,” Link says.

Leah Garchik, a former San Francisco Chronicle columnist, paints, makes bowls, gardens and takes her small dog to visit the elderly. She says Sandy Close makes her feel like a sluggard.

A sampling of EMS activities and output