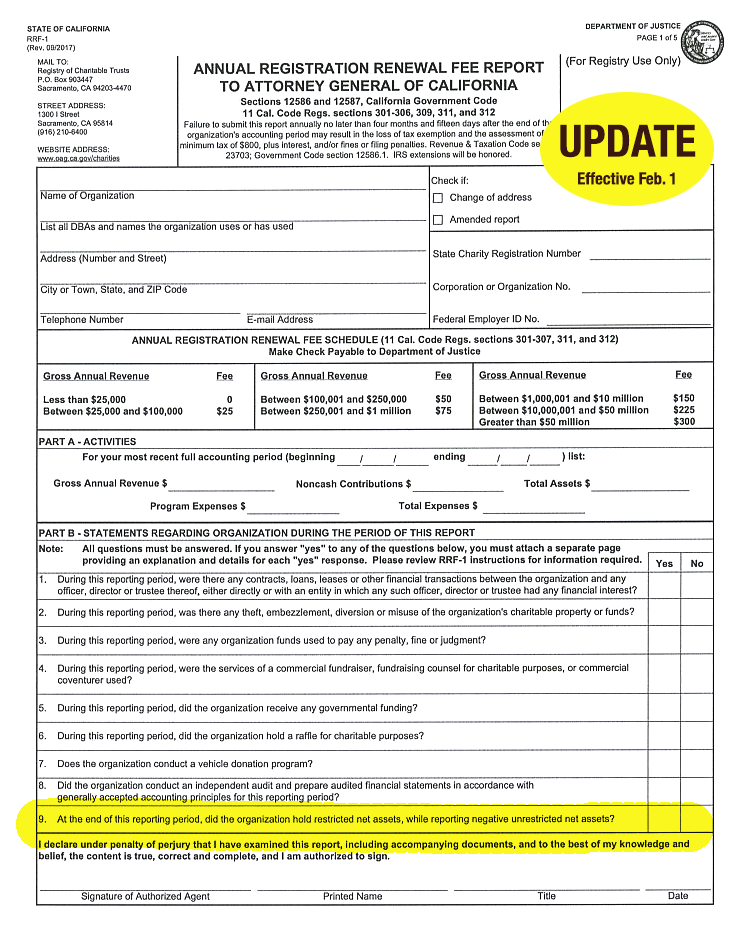

California nonprofits, as of Feb. 1, must answer a significant new question from the state Registry of Charitable Trusts. It’s question No. 9 on the one-page, yes-no, annual registration and renewal Form RRF-1:

California nonprofits, as of Feb. 1, must answer a significant new question from the state Registry of Charitable Trusts. It’s question No. 9 on the one-page, yes-no, annual registration and renewal Form RRF-1:

“At the end of this reporting period, did the organization hold restricted net assets, while reporting negative unrestricted net assets?”

No. 9 is of special interest to fiscal sponsors because, by definition, they hold their projects’ assets as restricted funds.

“Examples of restrictions,” say the No. 9 instructions, “are endowment funds, building funds, gifts for specific purposes, and fiscally sponsored projects.”

“I’d call this new question an early-warning system for the attorney general’s Registry of Charitable Trusts,” says Gregory Colvin, co-author of Fiscal Sponsorship: 6 Ways to Do It Right, who worked with the attorney general’s office to help draft the new question and review the instructions.

The instructions tell organizations filing IRS Form 990 to “refer to the Balance Sheet. If the line reporting unrestricted net assets is a negative number, and either or both of the lines reporting temporarily restricted or permanently restricted net assets are positive number (s), answer ‘yes.’ ”

And “yes” is the flag, Colvin says.

“For accounting purposes, if all your projects are positive but your unrestricted is negative, you may be running on internally borrowed money,” he says. “There can be reasons — like cash flow problems, lagging unbooked receivables or delayed reimbursements — at the time you file the report.”

Stephanie Petit, Colvin’s colleague and co-author of the just-published 6 Ways third edition, adds in an email, “Despite possible innocent explanations, if the charity has actually ‘borrowed’ from the restricted funds to shore up its general operating costs, that is obviously a problem.”

Those who answer “yes” have to explain their reasons in a written statement attached to the RRF-1. They have to confirm that the restricted funds were used “consistent with their restricted purpose” and explain why unrestricted net assets were negative at the end of the reporting period. The organization also must show proof of directors’ and officers’ liability insurance coverage, which assures the state that restricted fund owners have a source to recover money that may have been lost due to mismanagement.

Label conflict?

Another aspect of the revised RRF-1 is how it relates to two-year-old changes in national Financial Accounting Standard Board rules and the language of Form 990, where unrestricted net assets are labeled “without donor restrictions” and restricted net assets are called “with donor restrictions.” A colleague of Greg Colvin says he’s unsure how the language differences will play out, but expects the reported values will be the same, whether they refer to donors or not.

Colvin says he and his colleagues have been waiting for years for the attorney general to change RRF-1, ever since the catastrophic collapse of fiscal sponsor International Humanities Center in Pacific Palisades, Calif.

IHC was holding only $10,000 in restricted funds for its 200 projects — it should have been about $1 million — when it closed its doors unexpectedly in January 2012. The IHC debacle led to passage of a California statute, providing the attorney general’s office with the new enforcement tool.

In an August 2012 Nonprofit Quarterly article about IHC, reporter Rick Cohen suggests that if professional auditors were aware of the restricted-unrestricted disparities, “the organization would seemingly have had to be engaged in an all-but-intentional Ponzi scheme, knowingly using donations for projects’ future expenses to pay their (and IHC’s) past expenses.”

The IHC fiasco wasn’t a sui generis. It’s happened before, but with twists. Also in 2012, the projects of Help Is Here, an Arizona fiscal sponsor, said HIH kept project funds worth $300,000, claiming they were for extra services the projects said were never provided. The Fiscal Sponsor Directory covered the HIH story in a six-part news series. (Links to all the stories are at the end of Part 1.) That year, fiscal sponsor Christian Community Inc. in Fort Wayne, Ind., shut up shop with no explanation to its two projects, which lost $600,000.

Colvin hopes the revised RRF-1 form will benefit both the attorney general and fiscal sponsors by giving a heads-up that a problem may be brewing.

“With this new rule, the attorney general will be able to spot potential violations of the charitable trust doctrine,” Colvin wrote in the latest edition of 6 Ways, “and hopefully organizations will discuss their balance sheet internally before the year ends to resolve any discrepancies that might trigger a state investigation.”

Click here for the revised RRF-1 form and other Feb. 1 form changes that affect all California nonprofits. RRF-1s must be filed no later than four months and 15 days after the end of an organization’s accounting period, or May 15 for calendar year-filers.