The fast track to tax-exemption can take as little as 13 days — but at a price.

A saying, attributed either to a concept of commerce or gritty singer Tom Waits, goes: “You can have something fast, good or cheap. Pick two.”

The maxim could have been coined for the misbegotten IRS Form 1023-EZ: You can get tax exemption fast, properly vetted or cheap (using near-zero IRS manpower). All three, no.

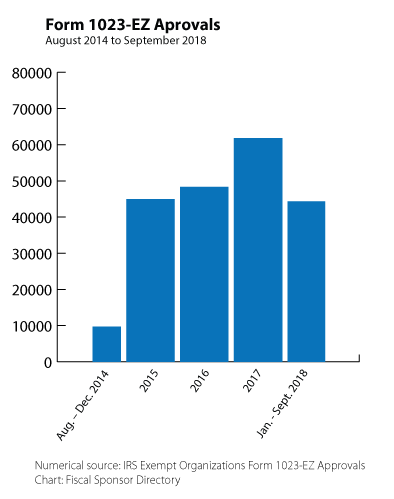

IRS introduced Form 1023-EZ in August 2014 to break the logjam of 501(c)(3) applications. It worked. The number of number of new tax-exempt groups has doubled in the last four years since EZ came on the scene.

Through the end of 2017, almost 165,000 organizations achieved tax-exempt status as EZ 501(c)(3)s, surpassing the 159,000 organizations that used more time-consuming long Form 1023. Another 44,000 groups joined the ranks via EZs in just the first nine months of 2018.

The high number of EZs suggests a surge in grassroots, hyperlocal charities likely focused on those communities’ most crying concerns. Yet the first wave of EZ applicants actually reflected pent-up service needs. About half them were founded decades ago, like the American Legion in Fairmont, Neb., incorporated in 1919, and the Beaux Arts Society in Mineola, N.Y., founded in 1857, incorporated in 1960 and tax-exempt in 2014.

EZ applicants in the past two years, however, have been mostly startups — nearly 4 in 5 had been incorporated for less than two years — and their names suggest they are focused on current needs: the Sustainable Coffee Institute in Spokane Valley, Wash., incorporated in 2017, for example.

Since 2014, opting for the online, streamlined, 2½-page EZ form instead of the 26-page Form 1023 has been a no-brainer for eligible applicants.

No need to write a narrative about their organization’s activities or submit financial data, substantiating documents or explanations. In fact, they can’t attach anything to their e-form, if they wanted to.

Warnings about EZ came early, even before its introduction. Such “rubber stamp approval” was likely to lead to a huge uptick in bogus applications, wrote Jonathan Spack, then executive director of pioneering fiscal sponsor Third Sector New England.

“When I first heard about this ‘cross my heart and hope to die’ approach I didn’t think the IRS was serious,” he wrote in “An Ill-Advised ‘Solution’ to a Serious Problem” (TSNEMissionWorks, April 2014). “Making exempt status automatic virtually guarantees that many who have self-selected out of the current daunting application — including some who would not pass muster today — will take advantage of the streamlined process.”

Of 183,729 organizations that applied via EZs from August 2014 through June 2018, 95% were approved. — Taxpayer Advocate Service

As IRS had hoped, approval times for 501(c)(3)s have fallen, but at a price: Many observers continue to insist that the easier process leads to erroneous, widespread approvals that threaten to damage the nonprofit sector’s reputation as a force for social good if nearly every applicant can be legitimized as a public charity with little scrutiny. Of 183,729 organizations that applied via EZs from August 2014 through June 2018, 95% were approved.

Early in 2018, IRS took a stab at addressing EZ critics’ concerns by requiring applicants to add a brief mission statement, but it’s too early to say if that change will affect the approval stats.

EZ vs. long form

EZ eligibility hinges on answering just a handful of questions: Does the applicant expect gross annual receipts of more than $50,000? Have total assets above $250,000? Was it organized in a foreign country? Ever had a 501(c)(3) revoked? Is it functioning as a church, school, HMO, hospital or private operating foundation?

Applicants that respond “yes” to any question must use the long form. But respond “no” to all, pay the $275 application fee — down from the original $400 when EZ was implemented — and tax-exemption is almost a done deal.

As a niche within the nonprofit sector, fiscal sponsors would seem unlikely to take advantage of EZ, principally because of the limit on gross receipts. Yet, of the 43 fiscal sponsors that joined the Directory in the last year, five used the streamlined form.

IRS hoped its introduction of EZ would ease the processing bottleneck that had been building for years. It did, and pretty fast. Times for approving long Form 1023s plummeted, from 315 days in mid-2014 to 113 days by the end of 2017. Not unexpectedly, the number of combined long- and short-form 501(c)(3) applications ballooned — from 65,000 in 2014 to 95,000 in 2017.

That might have made more work for IRS if the proportion of easier EZs hadn’t quickly eclipsed the long forms: One year after their debut, they were 15% of all 501(c)(3) applications. By the next year, they were 55% and last year 65%.

The IRS is handling many more applications but working faster. The agency’s 2017 report says reviewers spend an average 36 minutes determining whether an EZ applicant is eligible to use it, and they complete the approval process in 13 days. Regular Form 1023s take 2½ hours to review and 113 days to process.

EZ’s problems

Form EZ critics have been crying foul since its inception. The most vocal is the IRS’ own watchdog.

“The IRS continues to erroneously approve Form 1023-EZ applications at an unacceptably high rate,” wrote the Taxpayer Advocate Service, an internal, independent, IRS consumer advocate, in its 2017 year-end report to Congress. Bestowing charitable status on organizations that don’t meet basic tax-exempt requirements “outweighs the benefit of reduced Form 1023 cycle time,” said the report. “It damages the integrity of the tax-exempt sector.” Taxpayer Advocate Service’s reports to Congress in 2015 and 2016 expressed similar concerns.

Fiscal sponsors, with their unique, wide-ranging niche in the nonprofit sector, recognized early on that they could get caught in the fallout from EZs: An organization that received its 501(c)(3) without adequate scrutiny could set up shop as a fiscal sponsor, draw in projects and take advantage of them by not providing services, withholding funds, adding hidden fees and otherwise duping them for profit. Without scrutiny, they could exceed the $50,000 a year limit and the IRS would be none the wiser, at least for a while.

Scams could give fiscal sponsorship a hard-to-heal black eye that might undo years of hard-won efforts to prove its legitimacy.

“Form 1023 may be cumbersome, but it does a pretty good job of weeding out would-be charlatans and others who don’t meet the standard for 501(c)(3) status,” Spack wrote in 2014. But monitoring the large number of EZ applicants likely to descend on the IRS would create a far worse problem, he forecast. “Putting that genie back in the bottle is likely to prove extremely difficult.” And so it has.

National Taxpayer Advocate Nina E. Olson, head of Taxpayer Advocate Service, reported in her May blog that her staff had analyzed three years’ worth of EZ approvals from 25 states. They found that the articles of incorporation for 46% of the organizations lacked the purpose and dissolution clauses Treasury regulations require. Among those 49,000 new tax-exempt nonprofits, she added, were likely some that also weren’t complying with reporting requirements.

IRS automatically revokes an organization’s tax-exempt status if it fails to return a 990 for three consecutive years. Following that mandate isn’t much of a chore for an EZ: It need only submit a 990-N, an e-Postcard asking a few basic questions, including about name, address, EIN, principal officer and whether its annual gross receipts are below $50,000. No need to break down revenue and expenses as on the 990 or even the 990-EZ.

An organization EZ-approved in 2014 that didn’t submit a 990-N for three years wouldn’t lose its status until 2018, Olson noted. In fact, she said, a whopping third of the 15,000 organizations granted 501(c)(3)s via EZs in 2014 did have their status automatically revoked in 2018 for skipping the skimpy 990-N.

“Some might welcome these automatic revocations as a partial solution to the problem of erroneously granting exempt status in the first place,” she wrote. “I have a different perspective. … Even if its exempt status is automatically revoked, thereby ‘solving’ the problem of an erroneous Form 1023-EZ approval, there may be no accountability for assets the organization accumulated during the years it held exempt status.”

Her staffers’ study of 2015 EZ approvals found that 23% of the organizations had inadequate dissolution clauses. One had no purpose clause at all in its articles of incorporation.

Efforts to change EZs

Olson told Fiscal Sponsor Directory she issued a directive to IRS in September 2016: Change EZs so applicants must include a narrative of planned activities and submit their organizing documents. IRS agreed to implement the narrative requirement, but, says Olson, “the Deputy Commissioner rescinded the portion of the [directive] that would have required organizations to submit their organizing documents.” Without those, “reviewers can’t easily check key clauses of the articles of incorporation to determine whether they meet the requirements for tax-exempt status.”

More than two years after the directive, IRS added a text box to Part III of the EZ form requiring a description of the applicant’s mission or most significant activities. However, the text is limited to a paltry 225 characters — fewer than the characters in this paragraph.

Still, Olson says the narrative requirement is somewhat helpful. “It forces organizations (and professionals assisting them) to think through and articulate their mission. But it’s an incomplete solution. And no matter how an organization describes itself, it’s still required to meet the statutory and regulatory requirements for section 501(c)(3) status.”

For example, if the organization is a corporation, she points out, its articles of incorporation must have an purpose clause that meets one or more of the IRS’ requirements for exemption — charitable, scientific, literary, educational, etc. Also, many states require the articles to describe how an organization’s assets will be distributed if it dissolves: To be “acceptable,” they must go to one or more exempt purposes.

IRS admits EZ has its problems, but it is moving glacially to correct them. Its first-year report copped to shenanigans: 41 groups submitted more than 10 applications each. Four of them sent in more than 100 each and six tried to palm off more than 50.

The report acknowledged risks EZs pose: less IRS involvement with applicants; insufficient information on the form to make accurate determinations; greater chance of fraud; the perception that applicants might be treated inconsistently; and possibly inadequate application processing. To mitigate the risks, said the report, staff were scrutinizing 3% of EZ applications for problems. They found enough mistakes — wrong EINs, for example — that the approval rate in the sampling dropped from 95% to 77%.

Four years after that first EZ report, IRS published its “exempt organizations accomplishments” for 2017 and confirmed the risks: In a random selection of 1,182 EZ applications approved that year, it found staff should have reviewed the answers on more than half (51%) before giving them the thumbs-up. The IRS concluded the EZ application needed modification and added the 225-character description requirement.

The nonprofit sector continues to pressure the IRS to fix EZs. In April, the House Committee on Ways and Means was considering a Taxpayers First Act that amends the IRS code. David L. Thompson, vice president of public policy for the National Council of Nonprofits, wrote the committee asking it to revoke 1023-EZ and replace it with a form that “will better protect the public from scam artists.” The act, which passed the House, moved to the Senate in July, where it languishes.

“Our letter sought to put the problem on their radar,” Thompson wrote the Directory. “But the House didn’t add any language to fix the problems. So far Congress has shown little interest in fixing the challenges caused by the EZ.”

Taxpayer Advocate Olson says the burden of change is on IRS.

“Fixing these EZ ‘challenges’ doesn’t require legislation,” she says. “The IRS created the EZ requirements and can change them at any time. Congress generally doesn’t get involved in issues like this that don’t require changes in law. But if the IRS continues to automatically approve a lot of nonqualifying EZ applications, instances of abuse will continue to grow and Congress may eventually get involved to force the IRS to fix the system.”

Meantime, Taxpayer Advocate Service continues to track EZ data. In its October blog, it reported that even the most basic disqualifying answers seem to elude IRS reviewers. From April through June, they approved EZ applications from 18 churches and 21 organizations with LLC in their names — organizations that may qualify for tax-exempt status but must fill out long-form 1023s.

“We don’t think this is a losing battle,” Olson says. “The IRS has a new commissioner who can change these policies, and I think the data make a compelling case for change.”

Additional sources to help track 1023-EZ approvals and related matters:

Exempt Organizations Form 1023-EZ Approvals Searchable IRS database of approvals, August 2014 through June 2018. Includes some approved organizations’ websites that show articles of incorporation.

Tax Exempt Organization Search Searchable IRS database that includes automatic revocations.

National Taxpayer Advocate’s 2017 Annual Report to Congress Includes study of a representative sample of approved Form 1023-EZ applicants from 24 states.

Marjorie Beggs is Fiscal Sponsor Directory manager and San Francisco Study Center senior writer and editor.

Lise Stampfli, San Francisco Study Center art director, created the digital illustration for this article.