Political advocacy by nonprofits has taken on a new urgency since Donald Trump took office. For nonprofits, it’s a natural impulse to want to help create progressive change.

To what extent lobbying on specific legislation is allowed under current laws was the subject of the “Are You Ready for Elections and Advocacy in 2018?” workshop at the National Network of Fiscal Sponsors meeting in New Orleans in October.

The subject has been on fiscal sponsors’ radar for some time. It was a topic at the Northern California regional meeting in July, and the subject of a webinar that fiscal sponsor Independent Arts and Media commissioned from the NEO (Nonprofit and Exempt Organizations) Law Group.

Nancy McGlamery, a principal at the Adler & Colvin law firm in San Francisco, told her audience of fiscal sponsors from around the country that one section of U.S. Tax Code — 501(h) — simplifies the process of establishing compliance with IRS lobbying rules, greatly diminishes the severity of sanctions for violators and reduces the chilling effect on activity due to vague rules capriciously enforced that nonprofits have long contended with.

The rules are spelled out for 501(c)(3)s that elect to file for 501(h) status — accomplished simply by filling out the IRS Form 5768 that asks for little more than the organization’s name, address and tax ID number.

IRS RULES ON SPENDING FROR LOBBYING

Limits remain on what nonprofits can do, with or without 501(h) status — campaigning for or endorsing a candidate, for instance, are always verboten — but once an organization has elected 501(h) status, the law specifies to the dollar how much it can spend on lobbying, and what, in the eyes of the IRS, defines lobbying work.

The percentage of a 501(c)(3)’s budget the IRS allows it to spend on lobbying under 501(h) status varies according to the budget size. The IRS sees lobbying as either “direct” or “grass roots.”

A nonprofit with a $500,000 budget can spend up to 20% of that, $100,000, on lobbying. For budgets of $500,000 to $1 million, the percentage drops to 15. Budgets from $1 million to $1.5 million are limited to 10%, and for even bigger budgets, it’s 5%.

You can’t spend more than $1 million on lobbying. At the above rates, that threshold wouldn’t be reached until the organization’s annual budget hits $17.5 million. Exceed the allowed percentage and pay a 25% penalty on the overage. An organization that exceeds its limits by 50% or more for four years running loses its nonprofit status (https://tinyurl.com/IRS4911).

“Generally,” Rosemary E. Fei, of the Adler & Colvin law firm, said in lobbying guidelines she wrote in October 2014: “For charities that are eligible and have total exempt purpose expenditures of less than $35 million to $40 million, the benefits of electing Section 501(h) substantially outweigh any disadvantages.”

Private foundations and churches are not eligible to file for 501(h) status.

IF NO 501(H) …

A 501(h) fiscal sponsor can maximize its projects’ ability to do advocacy. As long as the sponsor stays within the limits of its allocation ꟷ based on its budget ꟷ a project under its wing potentially could devote more spending to lobbying than its own budget would otherwise permit. If some of the sponsor’s projects don’t do any lobbying, the sponsor can shift the allowable amount of their budget to its politically active projects, McGlamery said.

Without 501(h) status, a nonprofit’s ability to be politically active falls into a much murkier realm. The law, in place since 1934, says that a 501(c)(3) is forbidden from devoting a “substantial part” of its work to influencing legislation.

Fei pointed out that for smaller organizations to dedicate up to 20% of their spending on lobbying “would clearly be considered a substantial activity, in excess of the level permitted under the ‘no substantial part’ test.”

Violating that provision in a single year can cost an organization its tax-exempt status, so nonprofits have traditionally erred on the side of caution.

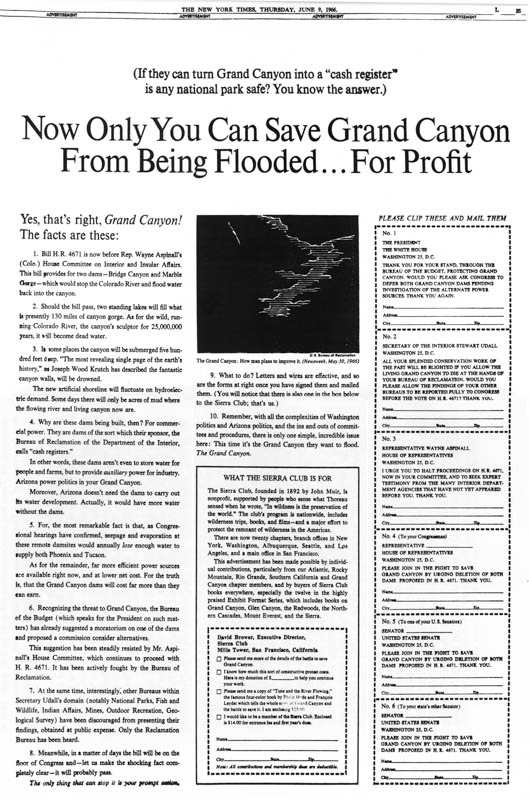

The Sierra Club learned the hard way in 1966 when it placed newspaper ads against building dams in the Grand Canyon and lost its tax-exempt status. The Sierra Club is a 501(c)(4) now, a “social welfare organization,” and donations to it are not tax-deductible.

Determining the level of activity that constitutes a “substantial part” of an organization’s work, however, “is entirely subjective,” Professor Jill S. Manny, executive director of NYU’s National Center on Philanthropy and the Law, wrote in a 2012 Case Western Reserve Law Review study.

501(h) status enhances the ability of projects to advocate for their causes. Housing Rights Committee of San Francisco is a project of the S.F. Study Center. Courtesy of Housing Rights Committee of San Francisco

THE ‘SMELL TEST’

The Substantial Part test, Manny wrote, is “a ‘smell test’ … blurry and perplexing … quite vague and provides almost no guidance to an organization wishing to influence legislation in furtherance of its exempt purpose without jeopardizing its exempt status.

“Restrictions on lobbying under 501(c)(3) are ambiguous, confusing and ineffective,” she continued. She cited IRS studies that found the restrictions more often prevent legitimate lobbying by cautious, law-abiding organizations than abuse of the system.

McGlamery said that without clear definition from the IRS of “no substantial part” of an organization’s activity, common practice among 501(c)(3)s is to devote no more than 5% of activity to advocacy work.

A 2013 study found that nonprofits were more than six times as likely to do advocacy if they had 501(h) status, but very few nonprofits did (1.3%, or fewer than 13,000 nationwide in 2009, according to the National Center for Charitable Statistics cited in Manny’s report).

“The strange disinterest in this helpful safe harbor is hard to explain,” Manny wrote.

Brice McKeever of the National Center for Charitable Statistics said that the center has not updated that 2009 data.

Jesse Lecy, an associate professor at Arizona State University School of Community Resources and Development, who has been part of a project culling data from the 65% of nonprofits that file tax forms online, estimates “about 3%” are 501(h)s, though conceding his sample may skew toward larger nonprofits.

And IRS data for 2014 show that 10,226 of the 201,775 nonprofits that filed Form 990 — 5% — answered “yes” on Part IV, Line 4, which asks if the organization engaged in lobbying or had 501(h) status.

HOW 501(H) WORKS

McGlamery said that Adler & Colvin invariably recommends filing the one-page IRS form 5768 to elect 501(h) status. Among its attributes, she pointed out, is that it carries no obligation to actually lobby, so organizations can flip it on and off like a light switch, lobby or not.

Moreover, “You can do more than 5%, with clear guidelines about what does and doesn’t constitute lobbying,” McGlamery said in an interview. A key distinction, she said, is the use of volunteers to do the advocacy.

The limitations on 501(h) activity are strictly on expenditures, so nonprofits can mobilize volunteers to great effect.

“If they (volunteers) have a substantial, outsized effect,” McGlamery said, “without being a substantial expenditure, under 501(h) election, it wouldn’t count for much.” But without 501(h) status, that same volunteer labor could count for plenty under the “no substantial part” test.

Nonprofits are increasingly interested in becoming politically active, Erin Bradrick of NEO Law Group in San Francisco wrote in an email to the Directory.

“We’ve seen two general patterns ꟷ organizations that have a social justice focus that have already been doing these activities but are feeling an imperative to ensure they are doing them correctly/compliantly (including newly formed organizations in response to recent events), and organizations across the spectrum that haven’t traditionally focused on these activities, but are thinking of beginning them (community foundations, fiscal sponsors, etc.),” Bradrick wrote.

California Association of Nonprofits, in a mid-January pitch touting its insurance services, noted: “In these stormy times, a remarkable 42% of California nonprofits report that they are increasing their public policy advocacy.”

“Backlash from the IRS intervention was probably one of the important factors in staving off the dams,”

“The Sierra Club realized it was far more concerned about a canyon than about tax status, the American public, it turned out, did not wish the tax man to jeopardize the world’s only Grand Canyon.” — David Brower, Sierra Club

2 TYPES OF LOBBYING

Lobbying is any effort to influence legislation. Thus, advocacy for or against an administrative policy falls outside that definition. The IRS categorizes lobbying activity as either “direct” or “grass roots.” McGlamery went into some detail in her New Orleans workshop about what differentiates the two.

The IRS defines grass roots lobbying as outreach to the general public with a “call to action” targeting specific decision makers. Direct lobbying is communicating with government officials and staff to convey a position on specific legislation.

Once a ballot-bound proposal makes it to the signature-gathering stage, however, the general public becomes a legislative body, and public education advocacy is no longer considered “grass roots” but “direct,” McGlamery said. That transition in the legislative process is important to track because a nonprofit is limited to spending no more than 25% of its lobbying allocation on grass roots efforts.

84 YEARS OF LOBBYING LAWS

The 1934 “no substantial part” smell test law stems from a 1930 court ruling that Margaret Sanger’s American Birth Control League had violated its tax-exempt status by advocating against restrictions on contraception. In 1954, the Johnson Amendment — introduced by then-Sen. Lyndon B. Johnson — further refined the rules by prohibiting 501(c)(3)s from endorsing or opposing political candidates.

In 1976, Congress enacted Internal Revenue Code 501(h), which offers an alternative to the smell test, and IRC 4911, which sets the sanctions for exceeding its limits.

Congress left in place the key restriction against endorsing candidates. For instance, nonprofits can stage voter registration drives and host candidate forums, but all candidates must be included in such events, and a nonpartisan presentation is required.

Late last year, the NAACP recruited volunteers nationwide for a get-out-the-vote drive in the run-up to Alabama’s Dec. 12 election to fill the Senate seat vacated by now-Attorney General Jeff Sessions. In training its volunteers, the organization was careful to counsel them to simply urge Alabamians to vote. They could offer to arrange transportation to the polls, but had to always stop short of advocating for either candidate, the Democrat Doug Jones or Republican Roy Moore.

OTHER BENEFITS OF 501(H)

Besides clarifying spending limits on lobbying without endangering a nonprofit’s exempt status, McGlamery pointed out that the 501(h) emphasis on actual spending frees organizations to use whatever inexpensive tools might benefit their efforts. An email blast that costs nothing more than the staff time to put it together, she said, would count for much less, when weighed monetarily, than when viewed as a reflection of the organization’s overall activity.

Fei cited other advantages of 501(h) election: the freedom to endorse legislation when little is spent to promote that endorsement, offer public commentary on legislation if there’s no call to action, and to lobby without limits in “self-defense” (over matters relevant to a charity’s existence, duties, tax-exempt status and more).

Also, the penalties for overreaching are more forgiving. Without electing 501(h) status, failing the “no substantial part” test even once could cost a 501(c)(3) its tax-exempt status and 5% fines on both its entire lobbying budget and the same amount from its managers who approved the excess activity. With 501(h) status, however, the penalties would be 25% of the excess spending — but if the limits on both “grass roots” and “direct” lobbying were exceeded, the penalty would be on only the larger amount.

An organization risks losing its nonprofit status if it exceeds its limits for either category by more than 50% over a four-year period. Should a 501(c)(3) lose its tax-exempt status for excessive lobbying, however, a key distinction of 501(h) penalties is that it would not have the option of then becoming a 501(c)(4), which enables lobbying but takes away tax-deductibility for donations.

The late David Brower, the Sierra Club’s first executive director, recalled in a 1982 celebration of the organization’s 90th anniversary how its newspaper ads urging readers to write their representatives to oppose plans to construct dams in the Grand Canyon, “brought an immediate response from the Internal Revenue Service, a letter hand-delivered to Sierra Club headquarters in San Francisco the next day” that immediately cut off major contributions.

It took the IRS two years to reject the club’s “painstaking defense of its position,” Brower said, and the Sierra Club was still seeking redress through the courts and Congress as he spoke. But in the meantime “small, nondeductible contributions multiplied,” Brower said, and in the next three years, membership doubled to 78,000. (It’s more than 10 times that now, 838,953 as of November, the club said.)

“Backlash from the IRS intervention was probably one of the important factors in staving off the dams,” Brower said.

“The Sierra Club realized it was far more concerned about a canyon than about tax status,” he said, and “the American public, it turned out, did not wish the tax man to jeopardize the world’s only Grand Canyon.”

Mark Hedin is the Directory’s community reporter