Crowdfunding, the skyrocketing money-raising strategy, burst into the nonprofit sector and is becoming a fixture of fiscal sponsorship. This is the first of a series of stories on the phenomenon, looking at the nuts and bolts, who’s doing it, campaign case studies, and the benefits and risks for fiscal sponsors.

Fiscal sponsorship’s role in the boom

A fiscally sponsored community group went looking for $750 to paint a mural in downtown Memphis. Across the country, in Berkeley, a fiscally sponsored publishing house sought $150,000 to help support its operations while it moved toward becoming tax exempt. Both met their goals — even exceeded them — via crowdfunding.

Statista.com, which collects statistics and studies from 18,000 sources worldwide, says U.S. crowdfunding is expected to reach $1 billion in 2018 and to grow more than 10% a year through 2022. More than 67,000 campaigns in 2016 brought in an average $5,500. According to the research firm Massolution, 10% of those campaigns funded social causes, and NextGenCrowdfunding says donors and investors add their money to campaigns at 3,500 Internet sites internationally.

No one has tracked how many fiscal sponsors and their projects are using crowdfunding. But, at the accelerating growth of online fundraising campaigns, the numbers are likely substantial.

“I think there’s an expectation now among fiscally sponsored projects that crowdfunding is how you fundraise,” said Dianne Debicella, former senior program director for Fractured Atlas in New York, far and away the nation’s biggest fiscal sponsor with 4,000 arts and culture projects. “Many projects run multiple campaigns, and some are using crowdfunding as an annual appeal — it’s on a trajectory and isn’t going away.”

Fractured Atlas app

So many Fractured Atlas projects were crowdfunding — in six years it managed 2,900 campaigns on Indiegogo that brought in $13 million, all as tax-deductible contributions — that last March the fiscal sponsor took a bold step: It began rolling out its own crowdfunding app for its projects, “software to manage our own business,” its Website says. Fractured Atlas projects can use any crowdfunding platform they want, but only donations run through the app are tax-deductible.

In crowdfunding, donors go to an online site, or platform, where their money pools in support of a campaign. Campaigns come in all sizes and forms, for-profit, nonprofit and personal. Backers may invest thousands in multimillion-dollar for-profit real estate deals — Times Realty News reported that in 2015, $484 million poured into such deals in the United States via 140 crowdfunding sites. Others may pledge $10 to help install speed bumps near an elementary school, or add $25 to a fund for a down-and-out relative.

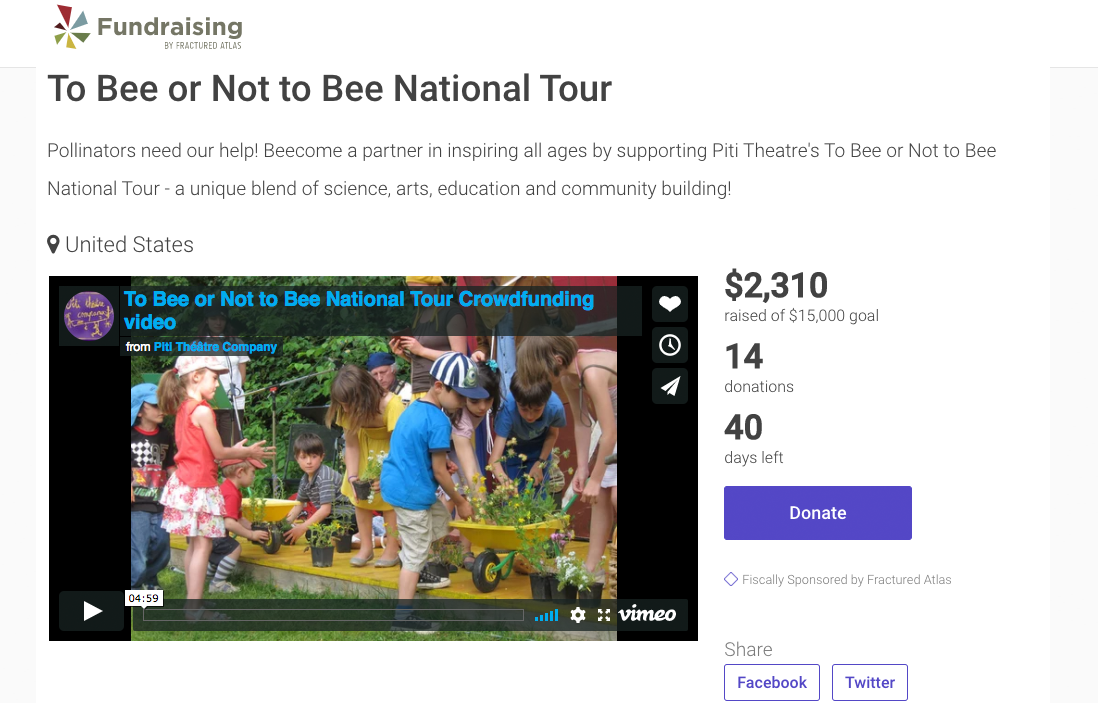

Piti Theatre, a fiscally sponsored project of Fractured Atlas whose To Bee or Not To Bee national tour includes demonstrations, is crowdfunding on the sponsor’s new platform.

Tax-deductibility adds a layer of complication to the process, so fiscal sponsors use only a handful of platforms — Indiegogo, Seed&Spark and Network for Good are among the most popular that welcome fiscal sponsors.

Kickstarter and GoFundMe are used primarily for arts projects and personal projects whose donors may not care about a tax deduction. Fiscally sponsored projects that choose to set up their own campaigns on these sites are most likely Model C projects with their own bank accounts. They can bypass their fiscal sponsor, forgoing tax deductibility as a donor incentive and paying the platform’s average 5% take but avoiding the fiscal sponsor’s fee, typically 10%.

Fiscal sponsors mix & match

Some fiscal sponsors with robust Websites mix and match crowdfunding and traditional donate-button fundraising. Supporters of the documentary “Normal Valid Lives” a fiscally sponsored project of 10-year-old Los Angeles fiscal sponsor The Film Collaborative, could make a tax-deductible donation to the doc at thefilmcollaborative.com or, later, join a Seed&Spark campaign that ultimately raised $22,453 during film production.

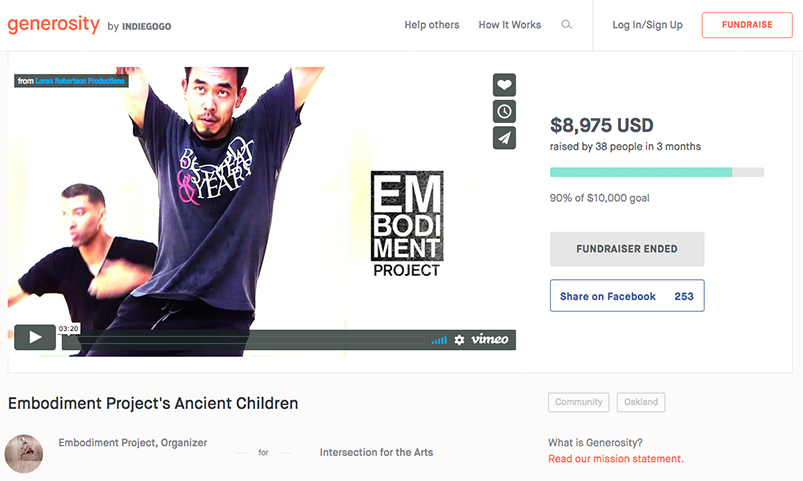

In San Francisco, the Website of venerable fiscal sponsor Intersection for the Arts has a donate button for its street dance, live song, theater and spoken word Embodiment Project, but in 2017 also helped it organize a crowdfunding campaign on the Generosity by Indiegogo platform that brought in almost $9,000 in three months.

Fractured Atlas’ move last year to offer its projects crowdfunding on its own platform is another way fiscal sponsors are spreading the use of this modern fundraising tool. It wasn’t the first to do so: New York-based fiscal sponsor ioby — in our back yards — has no ties to commercial platforms and has been crowdfunding on its own Website for almost 10 years.

This is crowdfunding 24/7: “If you are NOT interested in running a crowdfunding campaign,” says the ioby site, “we’re not the right fiscal sponsor for you.”

Since it launched in 2009, ioby has helped projects raise $4.1 million through 1,479 campaigns. Campaign goals average $4,000 and tax-deductible donations average $30. A group campaigning on the ioby site must either have its own 501(c)3 or be fiscally sponsored by ioby or another fiscal sponsor. In January 2018, ioby had 267 projects seeking crowdfunding donations.

FUSCO BROTHERS © 2018 J.C. DUFFY. Reprinted with permission of ANDREWS MCMEEL SYNDICATION. All rights reserved.

Typical campaign

A typical crowdfunding campaign posts its goal, when it started, how long it will run, amount raised to date, number of backers, how the money will be used, and profiles of the principals doing the work or making the art. Campaigns often include gifts tied to the donation amount, with the gift’s fair-market value subtracted from the tax-deductible amount — a $20 concert ticket reduces a $100 donation to $80 deductible.

Some platforms debit donors as soon as they give, turning over the money, less fees, to campaign managers as it comes in. Others wait until a goal is met to charge supporters’ credit cards, and, if it falls short, the campaign manager gets nothing.

Indiegogo offers both options, letting the campaign managers choose. At Indiegogo’s no-platform-fee Generosity site, campaigners keep all they raise, minus transaction fees, and get disbursements every three weeks. (Update: Since this story posted, Indiegogo sold Generosity to YouCaring, also a no-platform-fee site.)

Seed&Spark, focused on film campaigns, doesn’t charge donors unless a campaign reaches 80% of its goal; if it does, the campaign gets its money, less fees, within a week of the campaign’s end. Kickstarter charges donors’ credit cards only when the campaign reaches its funding deadline and meets its goal. The card isn’t charged if the goal isn’t met. At ioby, campaigns get everything they raise, minus fees, even if they don’t meet their goal.

Fees vary, but are ubiquitous: Most platforms charge around 5% of the amount raised and take another 3% or so for third-party transactions — credit or debit card, Pay Pal and the like. Many platforms also add 30 cents per transaction. A fiscally sponsored project contemplating a campaign that offers donors a tax deduction has to factor in those fees plus its sponsor’s fee. For sponsors profiled in the Directory, 10% is the median fee.

Those who study crowdfunding have this advice for newbies: No campaign succeeds without a lot of work to drum up interest in the venture before it starts and drive backers to the site throughout its run. Social media is essential in spreading the word, so most campaign pages have Facebook, Twitter, Tumblr, Pinterest and email links as well as URLs connected to the crowdfunding page that donors can paste into their Websites or blogs to bring others onboard.

Marjorie Beggs is Directory manager

Characteristics of crowdfunding donors

Record numbers of people reportedly are flocking to crowdfunding platforms. A November 2015 Pew Research Center survey of 4,687 people found that 22% had contributed to one or more campaigns. Survey participants were members of Pew’s American Trends Panel, randomly selected adult Internet-users who answer monthly Web surveys. The crowdfunding data were part of a larger study, “Shared, Collaborative and On Demand: The New Digital Economy.”

Most of the nearly 5,000 backers were college-educated 18- to 50-year-olds, and almost half their donations were in the $11-$50 range. While 2 in 3 gave to help a friend or family member in need, one-third donated to a school and one-third to a musician or other artist. Another third of respondents put money toward a new product or invention and 10% gave to help fund a business. (The donor percentages total more than 100% because many people gave to multiple campaigns.) Pew didn’t report whether the donations were tax-deductible.